The Little Match Girl: A Cry of the Unseen

A story not just about one lost child—but about all the ones we fail to see.

The Little Match Girl is more than a story; it is an indictment, a mirror, a whispered question in the wind: When suffering stands before us, why do we turn away?

The Last Light: Her Story

The cold is a creature with teeth. It gnaws at the tips of my fingers, burrows into my toes, coils along my spine. I press my hands to my mouth, breathing against the chapped skin, but my breath is a weak thing, shuddering from my lips like a moth too frail to fly.

The street is empty. No one looks at me.

They pass in fur-lined cloaks and woolen mittens, laughter rising in clouds of white against the dark. The windows glow, golden and full. I see them—families gathered around thick-bellied stoves, red-cheeked children pressing their hands against the glass, their faces bright with the kind of joy I have only ever seen from the outside. The scent of roasted goose drifts through a door that swings open, a momentary gift before it closes again, sealing warmth away from me.

I try to speak—“Matches, sir? Matches, ma’am?”—but my voice is brittle as frost. No one stops. They do not see me. Or perhaps they choose not to.

I do not know which is worse.

My basket grows heavier with matches unsold, my pockets light with hunger. I cannot go home. My father will not ask how cold I am. He will not ask if my stomach aches, if my fingers burn from the chill. He will ask only how much I have sold, and when I answer with silence, his hands will not be silent in return.

I press myself into the corner of a building, my back against the stone. The wind is merciless. I wonder how much colder a body can become before it stops feeling cold at all.

And then, in the darkness, an idea blooms. A single match. Just one.

I strike it against the wall, and the spark leaps, catching like a star in my palm. It flares, golden and alive, the light licking against the night.

And in that light, the cold dissolves.

A great iron stove stands before me, its belly full of fire. The warmth is thick, wrapping itself around me, kissing the tips of my fingers where frost had taken hold. I reach out—but before I can touch it, the match flickers, sputters, dies.

The stove vanishes.

The cold rushes back in, more brutal for the absence of heat. My breath stutters.

Another match.

This time, a great feast spreads before me. A table heavy with roasted goose, crisp-skinned and glistening, the scent curling into my nose like a promise. Candied apples, warm rolls with butter melting into their cracks, steaming broth thick with meat and potatoes. I have never seen such a feast, never even dared to dream of it.

I reach out, desperate—

The match dies.

The food is gone.

The hunger is worse now, because for a moment, I was full.

I fumble with the matches, striking another, and this time a Christmas tree rises before me, stretching tall into the night. The candles flicker on its branches, casting soft golden pools of light onto the snow. Silver ornaments sway gently, reflecting the fire’s glow. It is beautiful, more beautiful than anything I have ever known.

Then, something shifts. The candles begin to rise, higher and higher, lifting from the branches, floating into the sky like tiny suns.

No. Not candles. Stars.

I know what it means when a star falls.

Someone is dying.

The match gutters out.

The cold roars back.

My breath comes in shivers, my fingers curled tight around the last matches in my basket. My heart is a bird, frantic and trapped. There is only one thing left to do.

I strike them all at once.

Flames bloom, a thousand tiny suns cupped in my hands, and in their light—

She is there.

My grandmother.

Her face is soft and lined with love, her hands warm as she kneels before me, gathering me into her arms. She smells of bread and lavender, of stories whispered in the dark. She is the only one who ever held me, the only one who ever stayed.

“Take me with you,” I whisper. “Please.”

She smiles.

The warmth deepens, flooding through me, and I know—I will never feel the cold again.

The fire does not die this time.

It carries me away.

When morning comes, they will find my body curled in the snow, my lips parted in the shape of a dream. They will shake their heads, murmur something about the cruelty of winter, about the pity of it all.

But I am not there to hear them.

I am already gone.

The last match is still burning.

And I am finally warm.

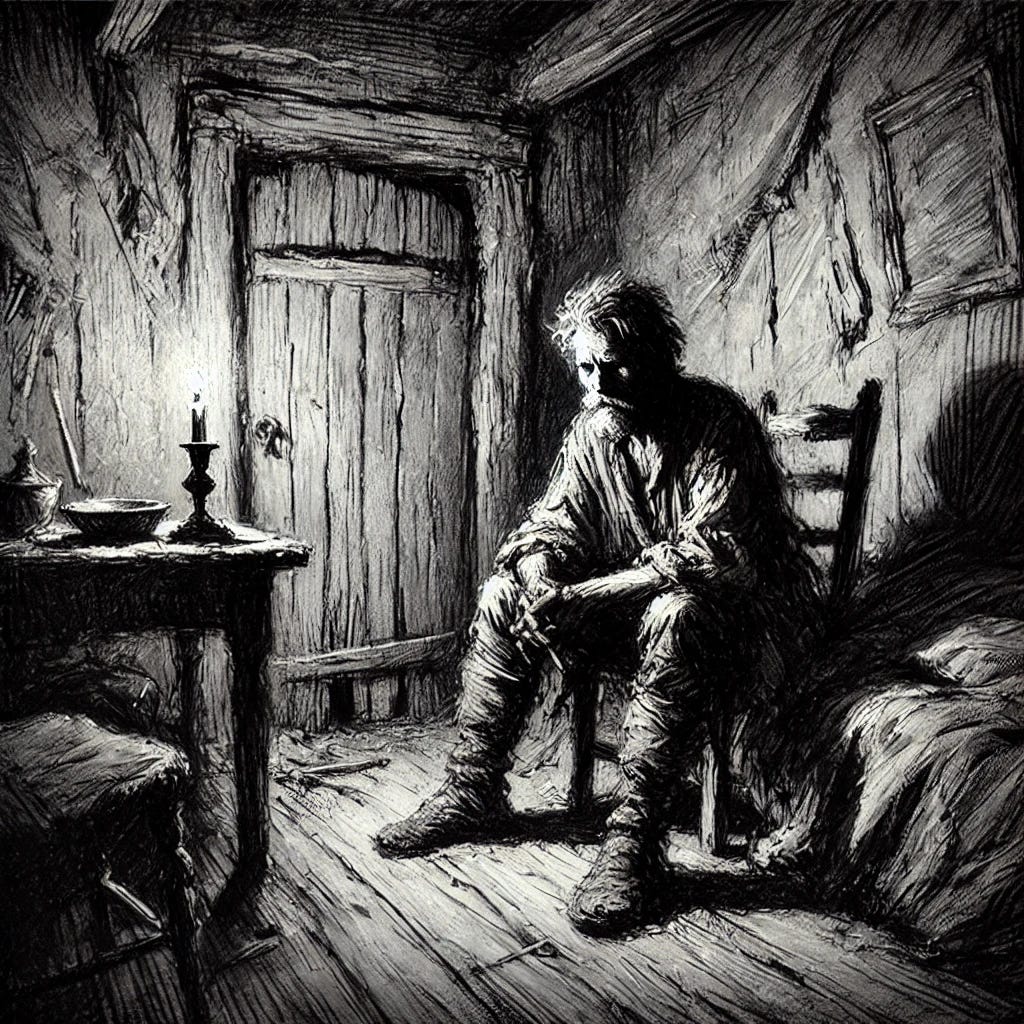

The Weight of Ash: Her Father’s Story

I wake to silence.

The fire in our grate has burned low, the embers pulsing like the last breath of something dying. The air in the room is thin and brittle with cold. I pull my coat over my shoulders, though it is no thicker than my own skin. Outside, the wind howls.

She should be home by now.

I push the thought away. The girl knows better than to come back empty-handed. I made sure of that.

I stretch my hands toward the weak heat, trying to thaw the stiffness from my fingers. When I was a boy, I did not know what it meant to be hungry. There was always bread on the table, a roof that did not leak. But a man can lose everything faster than he believes. Work disappears. Money vanishes. A life collapses, slow at first, then all at once.

And now, I am a man who must send his daughter into the street, because we are poorer than even hunger itself.

She does not complain. Not anymore.

She used to, at first. When she was smaller. She would cry, whimpering about the wind, about her aching feet. And what was I to do? Rock her in my arms? Whisper that everything would be all right, when I knew it would not?

Kindness is a luxury we can’t afford.

She is stronger now. She knows what is expected. I have not raised a weak child.

And yet—

Something twists inside me, sharp as a blade between the ribs.

I tell myself she is fine. That she has found shelter in some doorway, her matches sold, her pockets heavy with coins. She will return soon, and I will not have to raise my voice.

But the wind is too loud. The silence in this house is too deep.

And still, she does not come.

*

At dawn, I go looking.

The streets are hushed, wrapped in the kind of quiet that only snow can bring. My boots crunch against the frost.

And then—

I see her.

A small shape, curled against the stone of a building. Her hair dusted with snow. Her hands still clutching the empty air.

My feet stop moving.

No.

Not like this.

Not like this.

I kneel. Her skin is cold. I press my hand to her cheek, rough with frost. Her lashes are silvered with ice, but beneath them, her face is peaceful. A ghost of something lingers on her lips—

A smile.

I do not understand.

Her fingers are curled around something. A cluster of matchsticks, burnt down to blackened stems.

I close my eyes.

I should feel sorrow. I should feel rage. I should feel something.

But all I feel is hollow.

The wind blows, stirring the ashes between her fingers, carrying them into the dawn.

For the first time in years, I want to pray. But no words come.

So I kneel in the snow, my hands shaking, my breath sharp in my chest.

And I do the only thing I can do.

I sit beside my daughter.

And I let the cold take me, too.

The Girl in the Snow: A Bystander’s Story

I saw her.

I was leaving the bakery, a warm loaf cradled in my arms, the scent of butter and crust rising in soft curls of steam. The snow had begun to fall in the early afternoon, thick and heavy, muffling the sharp edges of the city. It was the kind of cold that seeped into the bones, the kind that made even the rich quicken their steps, tug their cloaks tighter.

And yet—she stood there, unmoving.

A small thing, barely more than a shadow, tucked into the corner of the street. Her dress was threadbare, her feet bare. Hair tangled, cheeks raw from the wind. Her hands trembled around the basket she carried, full of matches no one would buy.

“Matches, sir?” she whispered to a man in a fine coat. He didn’t look at her.

“Matches, ma’am?” she tried again. The woman barely paused before sweeping past, the scent of perfume trailing after her.

She swallowed, lowered her gaze, and tried again.

And again.

And again.

Each time, they walked past her as though she did not exist.

I did nothing.

I should have. I tell myself that now, standing here, watching her father kneel in the snow beside her.

He does not cry. He does not shake her, does not wail or call her name. He only kneels, his hands reaching out, then stopping before they can touch her.

She is frozen. Her body curled like a fallen bird, her lashes rimed with ice. In the dim light of morning, I see something strange upon her lips—

A smile.

Her hands are full of burnt matchsticks.

The people gather now, whispering among themselves. What a pity, they say. What a shame. Someone shakes their head, muttering about how cruel the winter can be. A woman clutches her child’s hand a little tighter, her fingers like a vise around the small wrist.

None of them stopped for her yesterday.

I did not stop for her yesterday.

The wind cuts through the street, wailing through the stone.

Her father is still kneeling. His shoulders are hunched, his head bowed. He is a man who has lost, and lost, and lost again. But this is different. This is something deeper.

He is not praying. He is not cursing.

He is only still.

A terrible stillness. A man who has looked upon the worst thing in his life and realized that in part, it is his own doing.

I shift, gripping the loaf in my arms, though it has gone cold. The weight of it feels heavy now, heavier than bread should be.

A single coin may have saved her. A crust of bread, a hand outstretched.

I tell myself I will not forget this. That next time, I will stop. That next time, I will reach out before the cold does.

But the truth is, I do not know if I will.

Because it is so easy, isn’t it?

To walk past suffering.

To let the wind swallow small voices.

To leave the match girl to the snow.

Lessons from "The Little Match Girl": A Mirror We Cannot Turn Away From

Today we confront a story that does not flinch. A story that does not offer comfort. Hans Christian Andersen’s The Little Match Girl is not a fairy tale. It is an indictment. A ghost that lingers long after the last match is burned out.

And I ask you—what will you do with it?

We could leave this room, let the warmth of other distractions carry us away, forget the girl in the snow. But if we do, then we become the figures who walked past her, the ones who averted their eyes and muttered, What a pity.

We must not turn away.

Lesson One: The Cruelty of Indifference

Did you notice that no one in the story harms the girl directly? There are no villains, no dark-hearted monsters lurking in alleyways. And yet, she dies all the same.

She dies because people do not see her.

Or rather, they choose not to.

And here is where we must ask ourselves the hardest question of all: Who have we ignored?

Who have we stepped around? Who have we dismissed as not our problem?

We live in a world where suffering is easier to ignore than ever. We scroll past it. We change the channel. We convince ourselves that someone else will help.

But if everyone walks by, the match girl dies in every age.

And if we are the ones who walk by, then we are complicit.

Lesson Two: The Lies We Tell Ourselves About Poverty

Consider this—had the girl stolen food, we would not call her a victim. We would call her a thief. Had she screamed in the streets, had she shaken her fists at the sky, we would call her mad.

We are most comfortable with suffering that is silent.

And isn’t that the tragedy? That she dies so politely? That she does not trouble anyone? That when they find her body, the morning moves on, the shops still open, the rich still feast?

What does that say about us?

What does it say that suffering is only seen as deserving of kindness when it is meek and quiet?

What does it say that people must be palatable in their pain before we will offer them help?

Lesson Three: The Fantasy of Hope, The Reality of Escape

The most devastating moment of the story is not her death. It is her happiness in dying.

With every match she strikes, she glimpses something beautiful—warmth, food, love. She does not want the world to change. She does not dream of revolution or justice.

She only wants to be warm.

And when she finally envisions her grandmother, when she finally sees the one person who ever held her with love, she knows that she must leave this world entirely.

And so, she does.

Ask yourself—why is the only escape from her suffering to die?

What kind of world is so cruel that death becomes the only kindness left to offer?

And who are we in that world?

Lesson Four: The Danger of Thinking ‘Not Me’

It is easy, isn’t it, to believe that we are not the problem? That we would have stopped, we would have bought a match, we would have saved her?

Maybe. Maybe not.

But here’s the truth: there are match girls in our world now.

Right now, there are children who go to sleep hungry. There are people shivering in the streets as we speak. There are countless who feel invisible, forgotten, unseen.

And not all of them are far away.

Suffering does not always look like bare feet in the snow. It does not always stand on the street corner with empty hands and hollow eyes. Sometimes, it sits beside you at work. Sometimes, it smiles at you across the dinner table.

It is the coworker who stays late because they have nowhere else to go. The friend who always laughs but never talks about themselves. The sibling who drifts further and further away. The parent who carries the weight of too much and tells no one.

And what are we doing?

Because the greatest tragedy of The Little Match Girl is not that she dies.

It is that she could have lived.

She could have lived if someone had given her a coin. If someone had offered her shelter. If someone had taken her hand and led her away from the cold.

She could have lived, if only someone had stopped.

And so, I ask you:

When you leave this room, when the comfort of routine settles back in, when you have the chance to stop—

Will you?

Or will you walk past?

Because the world will always be full of match girls.

And the lesson of this story is that it is not enough to pity them.

We must save them.